What Is The Makeup Of The Sun

Learning Objectives

By the end of this department, you will be able to:

- Explain how the composition of the Lord's day differs from that of Globe

- Describe the diverse layers of the Sun and their functions

- Explain what happens in the different parts of the Sun'southward atmosphere

The Lord's day, similar all stars, is an enormous ball of extremely hot, largely ionized gas, shining under its own ability. And nosotros do mean enormous. The Sun could fit 109 Earths side-past-side beyond its diameter, and information technology has enough book (takes upwards enough infinite) to agree about 1.3 1000000 Earths.

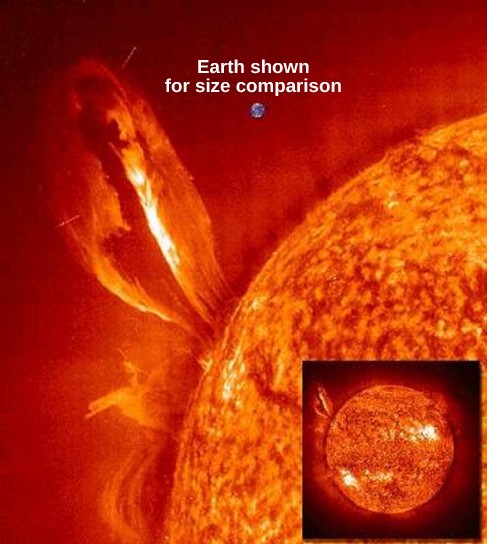

The Lord's day does not have a solid surface or continents similar World, nor does it take a solid cadre (Effigy 1). However, it does accept a lot of structure and can exist discussed as a series of layers, not unlike an onion. In this section, we describe the huge changes that occur in the Sun'due south extensive interior and temper, and the dynamic and violent eruptions that occur daily in its outer layers.

Figure 1. Earth and the Dominicus: Here, World is shown to calibration with office of the Sun and a giant loop of hot gas erupting from its surface. The inset shows the unabridged Sun, smaller. (credit: modification of work by SOHO/EIT/ESA)

Some of the basic characteristics of the Sun are listed in Table ane. Although some of the terms in that tabular array may exist unfamiliar to y'all right at present, you will get to know them equally you read farther.

| Tabular array i. Characteristics of the Sunday | ||

|---|---|---|

| Feature | How Found | Value |

| Mean altitude | Radar reflection from planets | 1 AU (149,597,892 km) |

| Maximum distance from World | 1.521 × ten8 km | |

| Minimum distance from Earth | one.471 × 108 km | |

| Mass | Orbit of Globe | 333,400 Earth masses (1.99 × 1030 kg) |

| Mean athwart diameter | Direct mensurate | 31´59´´.3 |

| Diameter of photosphere | Angular size and altitude | 109.3 × Earth diameter (1.39 × 106 km) |

| Mean density | Mass/book | ane.41 g/cm3 (1400 kg/m3) |

| Gravitational acceleration at photosphere (surface gravity) | GM/R 2 | 27.9 × Earth surface gravity = 273 m/s2 |

| Solar constant | Instrument sensitive to radiation at all wavelengths | 1370 W/thousand2 |

| Luminosity | Solar abiding × expanse of spherical surface 1 AU in radius | 3.8 × ten26 West |

| Spectral course | Spectrum | G2V |

| Effective temperature | Derived from luminosity and radius of the Sun | 5800 K |

| Rotation period at equator | Sunspots and Doppler shift in spectra taken at the edge of the Sun | 24 days 16 hours |

| Inclination of equator to ecliptic | Motions of sunspots | 7°ten´.five |

Limerick of the Sunday'south Atmosphere

Let'due south begin by asking what the solar atmosphere is made of. Every bit explained in Radiation and Spectra, we tin can use a star's absorption line spectrum to determine what elements are present. It turns out that the Sun contains the same elements as Globe but not in the aforementioned proportions. About 73% of the Sunday'due south mass is hydrogen, and another 25% is helium. All the other chemical elements (including those nosotros know and love in our own bodies, such as carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen) make up but ii% of our star. The 10 nigh abundant gases in the Sun'due south visible surface layer are listed in Table 1. Examine that table and notice that the composition of the Sun's outer layer is very different from Earth'southward crust, where we alive. (In our planet'south crust, the 3 most abundant elements are oxygen, silicon, and aluminum.) Although not like our planet's, the makeup of the Lord's day is quite typical of stars in general.

| Table 1. The Abundance of Elements in the Lord's day | ||

|---|---|---|

| Element | Percentage by Number of Atoms | Pct Past Mass |

| Hydrogen | 92.0 | 73.iv |

| Helium | 7.8 | 25.0 |

| Carbon | 0.02 | 0.twenty |

| Nitrogen | 0.008 | 0.09 |

| Oxygen | 0.06 | 0.80 |

| Neon | 0.01 | 0.sixteen |

| Magnesium | 0.003 | 0.06 |

| Silicon | 0.004 | 0.09 |

| Sulfur | 0.002 | 0.05 |

| Iron | 0.003 | 0.xiv |

Figure 2. Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin (1900–1979): Her 1925 doctoral thesis laid the foundations for understanding the limerick of the Sun and the stars. Yet, being a woman, she was not given a formal appointment at Harvard, where she worked, until 1938 and was not appointed a professor until 1956. (credit: Smithsonian Institution)

The fact that our Sun and the stars all have like compositions and are fabricated up of mostly hydrogen and helium was showtime shown in a brilliant thesis in 1925 by Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, the first woman to get a PhD in astronomy in the United States (Figure ii). However, the idea that the simplest low-cal gases—hydrogen and helium—were the most arable elements in stars was and then unexpected and and so shocking that she causeless her analysis of the information must be wrong. At the fourth dimension, she wrote, "The enormous abundance derived for these elements in the stellar temper is almost certainly not real." Even scientists sometimes detect it hard to accept new ideas that practice non agree with what anybody "knows" to exist correct.

Before Payne-Gaposchkin'southward piece of work, everyone assumed that the composition of the Sun and stars would exist much like that of Globe. It was iii years after her thesis that other studies proved beyond a doubt that the enormous abundance of hydrogen and helium in the Sun is indeed real. (And, as nosotros will see, the limerick of the Lord's day and the stars is much more typical of the makeup of the universe than the odd concentration of heavier elements that characterizes our planet.)

Most of the elements found in the Sun are in the form of atoms, with a small number of molecules, all in the form of gases: the Lord's day is so hot that no matter tin can survive equally a liquid or a solid. In fact, the Lord's day is so hot that many of the atoms in it are ionized, that is, stripped of one or more of their electrons. This removal of electrons from their atoms means that there is a big quantity of free electrons and positively charged ions in the Dominicus, making information technology an electrically charged surroundings—quite different from the neutral one in which you are reading this text. (Scientists phone call such a hot ionized gas a plasma.)

In the nineteenth century, scientists observed a spectral line at 530.iii nanometers in the Sun'due south outer temper, called the corona (a layer we will hash out in a minute.) This line had never been seen before, and so it was assumed that this line was the result of a new element found in the corona, rapidly named coronium. It was not until sixty years later that astronomers discovered that this emission was in fact due to highly ionized iron—iron with thirteen of its electrons stripped off. This is how we first discovered that the Lord's day's atmosphere had a temperature of more than than a million degrees.

The Layers of the Dominicus beneath the Visible Surface

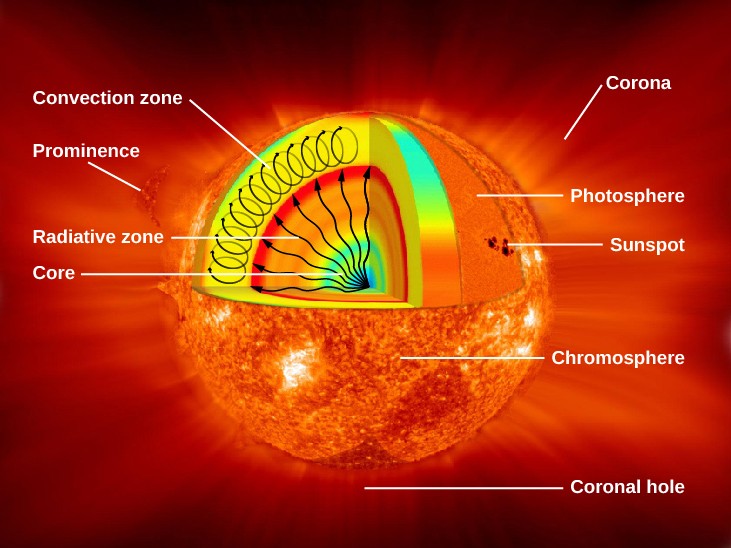

Figure three. Parts of the Dominicus: This analogy shows the different parts of the Sun, from the hot cadre where the energy is generated through regions where energy is transported outward, commencement past radiation, so by convection, and then out through the solar temper. The parts of the atmosphere are also labeled the photosphere, chromosphere, and corona. Some typical features in the atmosphere are shown, such every bit coronal holes and prominences. (credit: modification of work past NASA/Goddard)

Figure three shows what the Sun would look like if we could see all parts of information technology from the middle to its outer atmosphere; the terms in the effigy will become familiar to you equally yous read on.

The Sun's layers are different from each other, and each plays a part in producing the energy that the Lord's day ultimately emits. We will begin with the core and work our way out through the layers. The Sun'south core is extremely dumbo and is the source of all of its energy. Inside the core, nuclear energy is being released (in ways we will hash out in The Lord's day: A Nuclear Powerhouse). The cadre is approximately 20% of the size of the solar interior and is thought to have a temperature of approximately 15 million K, making it the hottest part of the Sunday.

Above the core is a region known as the radiative zone—named for the primary mode of transporting energy across it. This region starts at nigh 25% of the altitude to the solar surface and extends up to well-nigh lxx% of the way to the surface. The light generated in the core is transported through the radiative zone very slowly, since the high density of matter in this region means a photon cannot travel too far without encountering a particle, causing information technology to alter direction and lose some energy.

The convective zone is the outermost layer of the solar interior. It is a thick layer approximately 200,000 kilometers deep that transports energy from the edge of the radiative zone to the surface through giant convection cells, similar to a pot of boiling oatmeal. The plasma at the lesser of the convective zone is extremely hot, and it bubbles to the surface where information technology loses its heat to space. Once the plasma cools, it sinks back to the bottom of the convective zone.

Now that we have given a quick overview of the construction of the whole Sunday, in this section, we volition embark on a journeying through the visible layers of the Dominicus, outset with the photosphere—the visible surface.

The Solar Photosphere

Effigy iv. Solar Photosphere plus Sunspots: This photo shows the photosphere—the visible surface of the Sun. As well shown is an enlarged paradigm of a group of sunspots; the size of Earth is shown for comparison. Sunspots appear darker considering they are cooler than their surround. The typical temperature at the heart of a large sunspot is near 3800 K, whereas the photosphere has a temperature of about 5800 K. (credit: modification of work by NASA/SDO)

Earth's air is generally transparent. But on a smoggy day in many cities, it can become opaque, which prevents us from seeing through it past a certain bespeak. Something similar happens in the Sun. Its outer atmosphere is transparent, allowing us to wait a brusque distance through it. But when we try to look through the atmosphere deeper into the Sun, our view is blocked. The photosphere is the layer where the Sun becomes opaque and marks the purlieus by which we cannot encounter (Figure 4).

As we saw, the free energy that emerges from the photosphere was originally generated deep inside the Lord's day (more than on this in The Sun: A Nuclear Powerhouse). This energy is in the grade of photons, which brand their way slowly toward the solar surface. Outside the Lord's day, we can observe merely those photons that are emitted into the solar photosphere, where the density of atoms is sufficiently low and the photons tin finally escape from the Dominicus without colliding with some other atom or ion.

Every bit an analogy, imagine that you lot are attending a large campus rally and have constitute a prime number spot near the center of the action. Your friend arrives late and calls y'all on your jail cell phone to inquire you to join her at the border of the crowd. You determine that friendship is worth more than a prime number spot, so you lot piece of work your way out through the dense crowd to meet her. You can move only a short distance before bumping into someone, changing direction, and trying once again, making your way slowly to the outside edge of the oversupply. All this while, your efforts are not visible to your waiting friend at the edge. Your friend tin can't run into y'all until you get very close to the border considering of all the bodies in the fashion. So too photons making their way through the Dominicus are constantly bumping into atoms, irresolute direction, working their way slowly outward, and becoming visible simply when they achieve the atmosphere of the Sunday where the density of atoms is as well low to block their outward progress.

Astronomers take plant that the solar temper changes from almost perfectly transparent to almost completely opaque in a distance of just over 400 kilometers; it is this thin region that we call the photosphere, a word that comes from the Greek for "low-cal sphere." When astronomers speak of the "diameter" of the Dominicus, they mean the size of the region surrounded past the photosphere.

The photosphere looks sharp only from a distance. If y'all were falling into the Sun, you lot would non experience whatsoever surface but would just sense a gradual increment in the density of the gas surrounding y'all. It is much the same as falling through a cloud while skydiving. From far away, the deject looks every bit if it has a precipitous surface, but you do not feel a surface as you fall into it. (One big difference between these ii scenarios, nevertheless, is temperature. The Dominicus is so hot that you would exist vaporized long before you reached the photosphere. Skydiving in Earth'southward temper is much safer.)

Figure 5. Granulation Pattern: The surface markings of the convection cells create a granulation design on this dramatic paradigm (left) taken from the Japanese Hinode spacecraft. You lot tin see the same pattern when y'all heat upwardly miso soup. The correct image shows an irregular-shaped sunspot and granules on the Lord's day's surface, seen with the Swedish Solar Telescope on August 22, 2003. (credit left: modification of piece of work by Hinode JAXA/NASA/PPARC; credit right: ISP/SST/Oddbjorn Engvold, Jun Elin Wiik, Luc Rouppe van der Voort)

We might note that the atmosphere of the Sun is not a very dense layer compared to the air in the room where you are reading this text. At a typical point in the photosphere, the pressure is less than ten% of Earth's force per unit area at sea level, and the density is about 1 ten-thousandth of Earth'southward atmospheric density at ocean level.

Observations with telescopes show that the photosphere has a mottled appearance, resembling grains of rice spilled on a nighttime tablecloth or a pot of boiling oatmeal. This structure of the photosphere is called granulation (run across Figure v) Granules, which are typically 700 to thousand kilometers in diameter (about the width of Texas), appear as brilliant areas surrounded past narrow, darker (libation) regions. The lifetime of an individual granule is merely 5 to 10 minutes. Fifty-fifty larger are supergranules, which are about 35,000 kilometers across (about the size of two Earths) and last almost 24 hours.

The motions of the granules tin be studied by examining the Doppler shifts in the spectra of gases only in a higher place them (come across The Doppler Effect). The bright granules are columns of hotter gases rising at speeds of two to 3 kilometers per 2nd from below the photosphere. As this ascent gas reaches the photosphere, it spreads out, cools, and sinks down again into the darker regions between the granules. Measurements prove that the centers of the granules are hotter than the intergranular regions by l to 100 M.

See the "boiling" action of granulation in this 30-second time-lapse video from the Swedish Institute for Solar Physics.

The Chromosphere

Effigy half-dozen. The Sun'due south Atmosphere: Blended paradigm showing the three components of the solar temper: the photosphere or surface of the Lord's day taken in ordinary light; the chromosphere, imaged in the low-cal of the potent cherry-red spectral line of hydrogen (H-alpha); and the corona as seen with X-rays. (credit: modification of piece of work by NASA)

The Sun's outer gases extend far across the photosphere (Effigy 6). Because they are transparent to almost visible radiation and emit but a minor amount of light, these outer layers are difficult to observe. The region of the Sun'due south temper that lies immediately to a higher place the photosphere is called the chromosphere. Until this century, the chromosphere was visible only when the photosphere was concealed past the Moon during a total solar eclipse (run across the affiliate on Earth, Moon, and Sky). In the seventeenth century, several observers described what appeared to them equally a narrow ruby "streak" or "fringe" around the border of the Moon during a brief instant later the Sun's photosphere had been covered. The proper noun chromosphere, from the Greek for "colored sphere," was given to this scarlet streak.

Observations made during eclipses prove that the chromosphere is about 2000 to 3000 kilometers thick, and its spectrum consists of bright emission lines, indicating that this layer is composed of hot gases emitting light at discrete wavelengths. The reddish color of the chromosphere arises from i of the strongest emission lines in the visible function of its spectrum—the brilliant red line caused by hydrogen, the element that, as we have already seen, dominates the composition of the Sun.

In 1868, observations of the chromospheric spectrum revealed a yellow emission line that did not represent to whatever previously known element on Earth. Scientists chop-chop realized they had found a new element and named it helium (afterwards helios, the Greek word for "Sun"). It took until 1895 for helium to be discovered on our planet. Today, students are probably most familiar with it every bit the low-cal gas used to inflate balloons, although information technology turns out to be the second-most abundant element in the universe.

The temperature of the chromosphere is well-nigh x,000 K. This means that the chromosphere is hotter than the photosphere, which should seem surprising. In all the situations nosotros are familiar with, temperatures fall as 1 moves away from the source of heat, and the chromosphere is farther from the center of the Dominicus than the photosphere is.

The Transition Region

Figure 7. Temperatures in the Solar Temper: On this graph, temperature is shown increasing upward, and height above the photosphere is shown increasing to the right. Notation the very rapid increase in temperature over a very short distance in the transition region between the chromosphere and the corona.

The increase in temperature does non cease with the chromosphere. Above information technology is a region in the solar atmosphere where the temperature changes from 10,000 K (typical of the chromosphere) to nearly a 1000000 degrees. The hottest function of the solar atmosphere, which has a temperature of a million degrees or more than, is called the corona. Accordingly, the part of the Dominicus where the rapid temperature ascent occurs is called the transition region. It is probably but a few tens of kilometers thick. Figure 7 summarizes how the temperature of the solar atmosphere changes from the photosphere outward.

In 2013, NASA launched the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) to written report the transition region to empathize ameliorate how and why this sharp temperature increase occurs. IRIS is the outset space mission that is able to obtain high spatial resolution images of the dissimilar features produced over this broad temperature range and to run across how they change with time and location (Effigy eight).

Effigy 3 and the red graph in Figure 7 make the Sun seem rather like an onion, with shine spherical shells, each one with a unlike temperature. For a long time, astronomers did indeed think of the Sunday this way. Still, we now know that while this idea of layers—photosphere, chromosphere, transition region, corona—describes the big picture show fairly well, the Sun's atmosphere is really more than complicated, with hot and cool regions intermixed. For instance, clouds of carbon monoxide gas with temperatures colder than 4000 Thou have at present been found at the same peak higher up the photosphere as the much hotter gas of the chromosphere.

Figure eight. An image of a portion of the transition region of the corona, showing a filament, or ribbon-similar construction made up of many individual threads

The Corona

The outermost part of the Lord's day's atmosphere is called the corona. Like the chromosphere, the corona was first observed during full eclipses (Effigy 9). Different the chromosphere, the corona has been known for many centuries: information technology was referred to by the Roman historian Plutarch and was discussed in some particular by Kepler.

Figure nine. Coronagraph: This image of the Sun was taken March 2, 2016. The larger night circle in the center is the disk the blocks the Dominicus'south glare, allowing us to see the corona. The smaller inner circumvolve is where the Sun would be if information technology were visible in this image. (credit: modification of work by NASA/SOHO)

The corona extends millions of kilometers above the photosphere and emits most half equally much light equally the full moon. The reason we don't meet this light until an eclipse occurs is the overpowering brilliance of the photosphere. Just as bright urban center lights brand it difficult to come across faint starlight, and then too does the intense light from the photosphere hide the faint lite from the corona. While the all-time fourth dimension to see the corona from World is during a total solar eclipse, it can exist observed easily from orbiting spacecraft. Its brighter parts can now be photographed with a special instrument—a coronagraph—that removes the Lord's day'due south glare from the epitome with an occulting disk (a circular piece of material held then it is just in front of the Dominicus).

Studies of its spectrum show the corona to exist very low in density. At the bottom of the corona, there are only nearly ten9 atoms per cubic centimeter, compared with about 1016 atoms per cubic centimeter in the upper photosphere and xxix molecules per cubic centimeter at body of water level in Earth's temper. The corona thins out very apace at greater heights, where information technology corresponds to a loftier vacuum by Earth laboratory standards. The corona extends then far into space—far past Earth—that here on our planet, nosotros are technically living in the Dominicus'south temper.

The Solar Current of air

I of the nearly remarkable discoveries about the Sun's atmosphere is that it produces a stream of charged particles (mainly protons and electrons) that we call the solar air current. These particles flow outward from the Sunday into the solar arrangement at a speed of nigh 400 kilometers per 2d (almost 1 million miles per hr)! The solar wind exists because the gases in the corona are then hot and moving so rapidly that they cannot exist held back past solar gravity. (This current of air was actually discovered past its effects on the charged tails of comets; in a sense, nosotros can come across the comet tails blow in the solar cakewalk the way wind socks at an airport or curtains in an open up window flutter on Earth.)

Although the solar current of air textile is very, very rarified (i.due east., extremely low density), the Sun has an enormous surface area. Astronomers estimate that the Sunday is losing about 10 million tons of material each yr through this wind. While this amount of lost mass seems big by World standards, it is completely insignificant for the Sun.

Figure 10. Coronal Hole: The dark expanse visible nigh the Sun'south south pole on this Solar Dynamics Observer spacecraft prototype is a coronal pigsty. (credit: modification of work by NASA/SDO)

From where in the Sunday does the solar wind emerge? In visible photographs, the solar corona appears fairly uniform and polish. X-ray and extreme ultraviolet pictures, withal, show that the corona has loops, plumes, and both bright and dark regions. Large night regions of the corona that are relatively cool and quiet are called coronal holes (Figure 10). In these regions, magnetic field lines stretch far out into infinite away from the Lord's day, rather than looping back to the surface. The solar wind comes predominantly from coronal holes, where gas can stream away from the Sun into infinite unhindered by magnetic fields. Hot coronal gas, on the other hand, is present mainly where magnetic fields have trapped and full-bodied it.

At the surface of Globe, we are protected to some degree from the solar air current by our atmosphere and Earth's magnetic field (meet Globe as a Planet). Nevertheless, the magnetic field lines come into Earth at the north and south magnetic poles. Here, charged particles accelerated by the solar wind can follow the field downwardly into our atmosphere. As the particles strike molecules of air, they crusade them to glow, producing beautiful curtains of light called the auroras, or the northern and southern lights (Figure 11)

Figure 11. Aurora: The colorful glow in the heaven results from charged particles in a solar wind interacting with Earth'southward magnetic fields. The stunning display captured here occurred over Jokulsarlon Lake in Iceland in 2013. (credit: Moyan Brenn)

This NASA video explains and demonstrates the nature of the auroras and their relationship to Earth's magnetic field.

Key Concepts and Summary

The Sun, our star, has several layers beneath the visible surface: the core, radiative zone, and convective zone. These, in turn, are surrounded past a number of layers that make up the solar atmosphere. In society of increasing distance from the eye of the Lord's day, they are the photosphere, with a temperature that ranges from 4500 K to well-nigh 6800 Chiliad; the chromosphere, with a typical temperature of 104 K; the transition region, a zone that may exist only a few kilometers thick, where the temperature increases rapidly from tenfour K to 10vi K; and the corona, with temperatures of a few meg K. The Dominicus's surface is mottled with upwelling convection currents seen as hot, brilliant granules. Solar current of air particles stream out into the solar system through coronal holes. When such particles accomplish the vicinity of Earth, they produce auroras, which are strongest near Earth's magnetic poles. Hydrogen and helium together make up 98% of the mass of the Sun, whose limerick is much more feature of the universe at large than is the composition of Earth.

Glossary

aurora: light radiated past atoms and ions in the ionosphere excited by charged particles from the Sun, generally seen in the magnetic polar regions

chromosphere: the role of the solar atmosphere that lies immediately above the photospheric layers

corona: (of the Lord's day) the outer (hot) temper of the Lord's day

coronal hole: a region in the Sun's outer atmosphere that appears darker because there is less hot gas there

granulation: the rice-grain-like construction of the solar photosphere; granulation is produced past upwelling currents of gas that are slightly hotter, and therefore brighter, than the surrounding regions, which are flowing downward into the Sun

photosphere: the region of the solar (or stellar) atmosphere from which continuous radiation escapes into space

plasma: a hot ionized gas

solar air current: a period of hot, charged particles leaving the Sunday

transition region: the region in the Lord's day'southward atmosphere where the temperature rises very rapidly from the relatively low temperatures that characterize the chromosphere to the high temperatures of the corona

What Is The Makeup Of The Sun,

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/astronomy/chapter/the-structure-and-composition-of-the-sun/

Posted by: stultsfering.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Makeup Of The Sun"

Post a Comment